Hey!

Many of you guys asked me for a podcast or audio file to listen to instead of a video, so thankfully Substack offers this podcast feature to which I uploaded the audio of my talk. I'm also offering the slideshow below :)

A (rough) transcript of “A genealogy of network effects”

“I thought about doing something a bit different today for unlocking potential, which is to record a video. I didn't have time to write something good enough to publish. So I thought I'd reproduce this talk I gave at Qulture.Rocks. We're trying to do more of these tech talks where people teach something they know to the rest of the team, and I did one such talk a couple of weeks ago about moats and Network effects and so on and so forth, which was an open-ended talk, done off the cuff. So I thought about trimming it here and there and sharing.

I'm using this new tool called Loom, which just raised a big round from Sequoia. It's nothing groundbreaking. We've been using something different called Soapbox from a company called Wistia since about two years ago. It's honestly better than Loom. But, somehow, this Loom product got much publicity after the cool kids from the Valley (meaning Sequoia but a bunch of angels like the founders of Instagram and Front) invested in it.

Anyway, the first time I did this talk I named it "moats, network effects, and positive feedback Loops." This current version is more like a "Genealogy of network effects." One thing I do, when I try to understand something new (or deepen my understanding of something not so new to me) is to try to roughly figure out where it stands within a greater a corpus of knowledge. I think genealogy would be this tree structure that helps me understand this.

What got me to study moats and network effects

I've been really interested in studying more about moats, so as to figure out what makes an amazing company successful in the long run. I did a lot of Michael Porter rereading and then stumbled upon the works of this guy called Pat Dorsey's, which I've shared with you in the past (he's a value investor, of the Warren Buffet type). I also went back to Peter Thiel's Zero to One book, which touches on this tangential concept of monopolies, and how they arise and have seen more and more stuff about moats generally.

And network effects are a special type of moat that I think are pretty interesting to look at. And I was reading about network effects when I came across this article from NFX (a firm which is supposedly the expert in network effects-powered businesses). They're a venture fund and they tried to do this network effects map that in order to catalog all sorts of network effects.

Since reading about McKinsey's way of thinking and presenting their consulting work I became obsessed with this concept of MECE, which means Mutually Exclusive and Collectively Exhaustive, just a beautiful way of saying you're doing these categorizations in a way that doesn't mess with your mind [1]. Each category is independent of each other, just like a bunch of not-overlapping Venn diagrams (the categories are mutually exclusive). Also, the sum of all categories (all the Venn diagrams) is exhaustive.

The NFX article was helpful but could be much more helpful. It was very confusing. Just a weird Venn diagram with circles that seemed to be randomly thrown at a slide. So that just boiled my stomach. It didn't look MECE at all, and therefore it didn't really give me a framework with which to understand network effects.

To get up to speed, I brought this Robert Metcalfe quote that says, "In network theory," which is what preceded network effects, "The value of a system grows at approximately the square of the number of users of the system." This squared relationship between the size of a network and its value was named Metcalfe's law and it's kind of a corollary or something that's really used whenever people talk about network effects. Generally, if we think about Facebook, the idea is that the value of Facebook grows at the square the number of users of it, whatever that means, which I just can't grasp. You just get a sense of this very strong relationship between the size of a network and its value. I'm not a numbers person.

Why are Network effects important?

A company is generally worth the present value of its future cash flows. That's Finance 101, or maybe Valuation 101. It's pretty hard to grasp the impact of cash flows when these same cash flows - meaning the positive ones - are very much in the future, as they are with startups.

What determines the size and the direction of these future cash flows is the quality of the business, which comes from, in great part, how defensible the business is. What's generally accepted is that there is no economic profit, meaning a company's not going to make more money than it "should" because its competitors are going to eat away that excessive return. They're going to just bite and bite until there's nothing left.

What's understood as an economic profit is just basically the company making more money than it should. It means making more money than its risk-adjusted cost of capital, which is how much when investors generally debt or equity or whatever are willing to lend money to it for. The interesting thing is these economic profits, they may be possible or they may be bigger, the bigger these moats are.

What is a moat?

Moats as a concept became popular, I'd risk, because of Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger.

The literal definition of a moat is this lake that encircles a castle. In medieval times, the lake - the width of the lake and the depth of the lake, and maybe the presence of alligators or piranhas or something - would deter invaders from penetrating the castle. That's the idea of a moat.

The moat is your protection against these competitive invaders that want to eat away your economic profit. When we see Warren buffet talking about it, is he likes to chase businesses that have big moats, of course. The whole idea of what Warren buffet does is buying a big moat, wide moat, strong moat businesses, but he also looks for management that wants to widen, to strengthen, the moat every year. He likes the idea of deliberately widening and deepening the moat as sort of this strategic imperative of companies.

As we said, a moat is basically defense against competition. So what do we mean by competition?

When we talk about competition, we mean competition for profits. I think here Michael Porter helps a lot to understand who competes away our profits or who are the players that are trying to eat away our profits. His five forces model is the best I think to think about this. What he basically says is that there are five forces determining your economic profits. These are existing competitors who are currently in their market, new potential competitors who may join your market if they think it's attractive, your suppliers and your customers who are also bargaining with you and charging you more or paying you less and so on and so forth. Also the threat of substitutes, which is generally a degree of separation more. If we think about current competitors are these ... I think there's no clear line that really separates what's a competitor from what's a substitute.

If we look at Clayton Christensen's 'Jobs to be Done' framework, he's got the Innovator's Solution, which is this book here [author showing the book]. He's basically telling you that everybody that gets a job done competes for a market or, better, can be considered competitors. You may be doing, for example, your performance reviews in a system like Qulture.Rocks but you may as well do it in Excel or Access. These guys are like competitors, but we'd call them substitutes. These five groups or constituencies are our competing away your profits and fighting for it.

New entrants, they enter your market either because you have very low barriers to entry or not enter your market if you have high barriers to entry. This is a good way of thinking about how defensible. I'm not going to get into five forces or porter here but if you want, it's pretty easy to find stuff online about it. New entrants may enter your market as a function of how big are your barriers to entry. Your current competitors may compete more fiercely or less fiercely for your pool of profits. There are different market dynamics that make them more fierce or less fierce. For example, if you have assets that are highly specific, you might be incentivized to compete more fiercely because you can't do anything else with your assets.

Also, if there's a 'winner takes all' dynamics in your market or even the perception of a 'winner takes all' dimension, which sometimes perceptions and realities are not the same. I think I've argued before on the newsletter that I think the 'winner takes all' dynamics of right sharing is overblown. They will compete too fiercely. Another dynamic that drives up the internal competition is marginal costs. The smaller they are, the bigger than the incentive of players cutting prices for example because it just doesn't matter. Customer and suppliers, they also may take away your profits, the bigger their bargaining power against you or with you. So again, moats are a defense against competition.

What's interesting is that there are different types of moats.

A taxonomy of moats

As we talked about a bit earlier, Peter Thiel doesn't call them moats but he talks about these factors that enable monopoly-like businesses. I've talked before about Pat Dorsey who worked on this theme when he was at Morningstar and then he founded his own asset management company, like a long-only equities management company. He talks about four types. He talks about economies of scale. He talks about intangibles which are brand, eventually technology and also some regulation power or monopoly that you have. So the government is granting you a monopoly or a stronger position. He talks about switching costs and he also talks about Network effects, which are our focus here.

But I was reading this book by Hal Varian, who's the chief economist at Google. He has a very old book, oldie but goodie, called Information Rules. I think I cited it before. He doesn't speak quite exactly about moats, but he speaks about what makes strong competitive positions in the information economy. He basically has these two broad categories. One is locking, which is basically switching costs, how hard it is for me to switch products, and the other one is positive feedback loops. He talks about two subtypes of positive feedback loops, demand-side and supply-side economies of scale. I like this example much more because I think a brand is a fickle moat. I think regulation is an unpredictable moat. I think tech, it's hard to find tech that is really something else. I do think tech sometimes spills over to Network effects, which are a sort of positive feedback. IMHO, it is a better model.

So I like this and I was wanting to work with this taxonomy of moats.

Economies of scale are pretty simple. There is a type of supply-side economies of scale. They are the type of supply-side economies of scale. The more you produce, the cheaper your unit costs are. Most manufacturing businesses have that dynamic, also businesses that have high operational leverage, which is high fixed costs. Once they start producing more volume, unit costs fall abrupt thusly. For example, one sticker. I can produce one sticker for R$10. I can produce a thousand stickers for 20 cents. That is a sort of moat because it deters ... like if a competitor comes, he's probably going to start producing, I don't know, one or 10 stickers.

His cost is going to be very high. My cost is going to be very low and I can even drive him out because I might cut prices or whatever. I have this big protection against my new entrants especially. Switching costs prevent my customers from switching out of my product. There's a very good example, which is ERP software. It's so damning to install into and to implement, that people don't ever want to move out of it. These have very high switching costs and they give the supplier a lot of bargaining power because the supplier may want to raise prices by 10% of 20% a year and still don't weed out the customer base. For example, how easy it is for a customer to leave AWS or Heroku. You have deep integrations for your system.

You're going to think like a thousand times or you're going to think a lot before moving out. These businesses tend to have high bargaining powers with us and especially if these lines, like the best businesses, have very high switching costs, but they're a small line on my P&L. I'm even more incentivized to ignore a price hike. Then we get to the demand-side economies of scale. Well actually, supply-side economies of scale are also positive feedback. Maybe we should just ignore this slide. Let's talk a little bit about this. Hal Varian, he spoke about positive feedback, which Jim Collins calls the 'flywheel effect'. Hal described these two blocks, which is supply-side and demand-side economies of scale.

We already spoke about the supply-side, which is cost advantages attributable to scale. Demand-side economies of scale are what generally people call Network effects. This is pretty general. A network effect is when a product is worth more, maybe to each additional user, the joints, the more users this system has. This is a more working definition of Network effects but I think it's similar to Metcalfe's definition, which we showed you at the start of this. Hal also speaks about this. He says, "Whether real or virtual," so he's saying like either Facebook or maybe a telephone line network. Networks have a fundamental economic characteristic. The value of connecting to it depends on the number of other people already connected to it.

The value of me joining a social network depends on the number of people that are already in. He says this fundamental value proposition goes under many names; network effects, network externalities and demand-side economies of scale. The quintessential question that describes what a Network effect is, how valuable would new Instagram be if none of your friends were there? You have no reason to join whereas if everybody is in there, you have all the reasons to join because people are there. You'll have friends to connect and friends to stalk and so on. I think a good thing is to think about a better taxonomy of these positive feedback loops.

Hal Varian speaks about supply-side and demand-side economies of scale. On the demand side, I think we can generally have these two categories which are, you have demand-side economies of scale that have a user as a primary driver of value whereas you have other types of these demand-side economies of scale where users are not the primary driver of value.

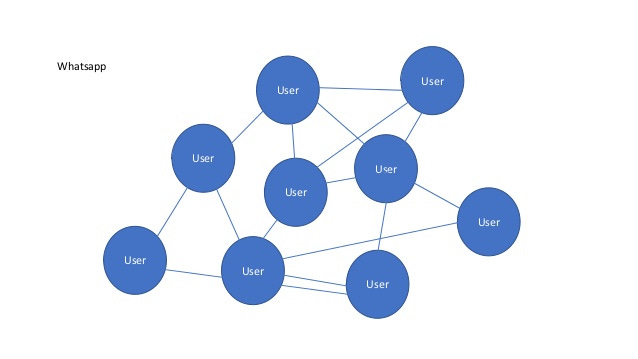

We're going to look at some of these types and I'm going to show you how and why and examples they're not the same. If we look at WhatsApp for example, the value of using WhatsApp or Telegram or Symphony is greater the more users are in and users are the primary lever of the value of entering this network. I want to use WhatsApp if, and only if, other people are inside WhatsApp.

It’s users as a primary value driver. Also, it doesn't matter to me if there are only users. Everybody that joins this network are users and only users, whereas if we look at Facebook, it's a different thing. I'm going to join Facebook because of other users and I have more incentives to join Facebook the more users it has, at least users that are relevant to me.

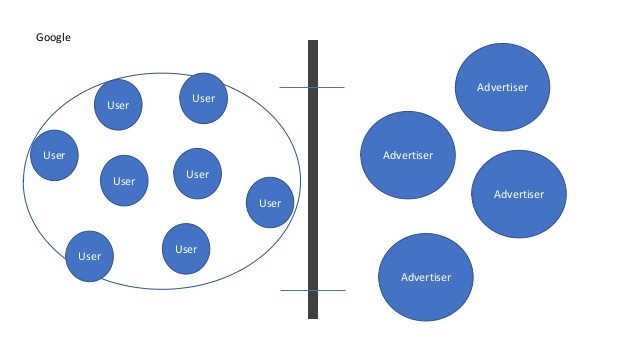

These network effects are almost geographically or social network limited. I'm going to join Facebook if people that are relevant to me are inside. There's also a different dynamic going on, which is the more users on this left side of the platform there are, the more advertisers there will be on the right side of the platform. This is not a network effect per se, but it is a positive feedback loop because the more users, the more advertisers, and the more advertisers, the more money Facebook makes. There are interesting specificities here, which is the fact that maybe in some ways, the more advertisers there are on the right side, maybe the worse this experience becomes to the users on the left side.

Also maybe, the more advertisers there are on the right side, advertisers don't want the competition. There may be even negative Network effects on the advertiser side. Ad costs go up and you may crowd out advertisers. Google is even different.

When I use Google, I don't care if other people that are relevant to me use Google. Nonetheless, the quality of the product becomes better, the more people use it. That's what I call this Network effect where the user is not the primary driver. When users join, the quality gets up but the driver of Network effects or demand-side economies of scale, it's actually the quality of the model and not the people. That's the only difference. In the other sense, there are also two sides of the platform and so on and so forth.

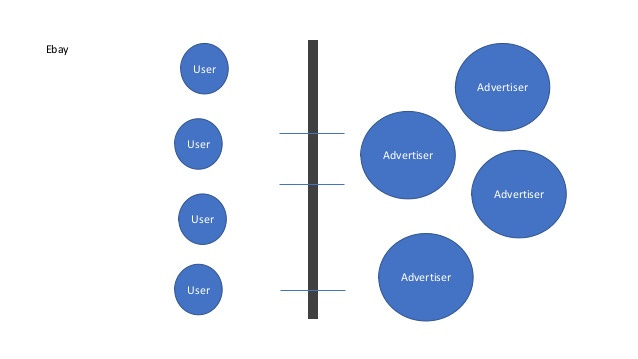

A part of it works just like Facebook. On eBay, it's actually buyers on the left side and sellers on the right side. I don't care if there are other buyers on my side. I just want to find the products I'm looking for. The more people on one side, the more people on the other side.

There's not a lot of a relationship between the more people on the right side, the more people on the right side. It's across. Maybe the more people on the right side, the more people on the left side, and the more people on the left side, the more people on the right side. This is a positive feedback loop, but it's quite different.

Quora for a change is like Google. I joined Quora to get interesting content and to get my questions answered. I don't really care about the social aspect of Quora. We may argue that there is a social aspect like status-seeking, but in some ways, I want answers.

I want content. The quality and the network effect is more driven by quality, which is therefore driven by users, but not users directly. Users are primary drivers. This is to give you a sense of what I think are primary versus non-primary drivers. I think the type of network Metcalfe was thinking about was a network that has users as the primary drivers of value for the network. I don't think he was thinking about platforms, like these two-sided platforms or these multi-sided platforms.

We're really trying to break ground here and figure out a better taxonomy of this thing because when people coined the Network effect term, there wasn't really anything of the sort of platforms or maybe something. So thinking about network effects as this whole positive feedback group, I think it's not helpful. I'm trying to give you a better way to think about this.

When Jim Collins talks about flywheels, he may be talking about positive feedback in how variants taxonomy or he may be talking about demand-side economies of scale, which are like your Network effects. When he talks about Amazon for example as having a very strong flywheel, it's a mix between both because now ... Amazon has the “selling their own goods” part of their eCommerce operation.

There's this clear supply-side economy of scale dynamics but they're also operating in a marketplace and on that side, there are demand-side economies of scale in terms of a two-sided platform where the more buyers, the more sellers, and the more sellers, the more buyers. There's a mix between the two. Reforge, which I wrongly typed, regorge calls these macro goal growth loops. I think they go on just too far with this. I don't like their definition. Jim Collins, a flywheel is a company with positive feedback. Amazon's fly was very normal or whatever example we showed. The more customers, the lower the prices, the lower the prices, the more customers come in. The more customers come in, the lower the prices and so on and so forth, until they become a trillion-dollar company.

These positive feedbacks or flywheels, I think they have different flavors and people want to say every company is a flywheel. I heard this outrageous example the other day, which is, "The more product I sell, the more revenue I make, and the more revenue I make, the more salespeople I hire." This is stupid. Every company is like this. I don't think that's a very strong form of a positive feedback loop. A strong form of a positive feedback group is a winner takes all kind of a dynamic. I think Windows was a good example because everybody's going to develop for the winner. I don't think it is a winner takes all like a perfect winner takes all dynamic. For example, I use Mac and a lot of people use Windows. Some people use Android, some people use the iPhone. I think there's maybe room for a duopoly or maybe an oligopoly. Surely not for a lot of competitors. It may be not a winner takes all dynamic, but you must get up to a certain scale or critical mass before you're something, before you pass the surf and get to calmer seas.

Going back to moats, I think a good way to think about this is like three types of moats: Regulation, brand, which is a weak one, and positive feedback. Within positive feedback, there are supply-side economies of scale, which are what we think about when we think about “economies of scale”, and demand-side economies of scale, which are, roughly, what we think about when we think about network effects.

I really hope I have helped you better understand moats and network effects. It helped me a lot, anyway. I'm trying to be a Richard Feynmann devotee here in trying to explain stuff as a way to understand stuff. I'm sure my mom or my grandma wouldn't understand a single second of what I talked about. I have a lot of progress in the making. But I think my understanding got better by trying to explain this to Q.Players and now to you guys.

Thank you so much.”

Notes

[1] If you want to learn more about MECE, there's an interesting book called "The Pyramid Principle" by a lady called Barbara Minto, which I think is pretty interesting as a handbook of how to organize your thinking and how to write. I think MECE comes from Minto.