Depositor's Dilemma

Or, thoughts on The Great Silicon Valley Bank Run

This weekend has been marked by the failure, on Friday, of Silicon Valley Bank, where a huge number of startup founders and investors - including yours truly - held money, and the announcement, on Sunday, that depositors would be made whole even as equity and bondholders are getting most definitely wiped out. Here are some thoughts on The Great Silicon Valley Bank Run.

Bank run

Imagine your company has some money in a checking account, in a bank, and you want to withdraw that money to pay for something, such as payroll. But, figuratively, when you get to the bank you see a long line of people waiting to take their money out too. You might start to worry - why are so many people in line to take their money out? Is there something wrong with the bank? Should I be doing the same?

The thing with western banks is, if enough people start to worry and decide to withdraw their money, there's no money for everybody. And when customers start to withdraw their money in tandem, trying not to be the ones left with the bag, it's what's called a "run on the bank." Everyone rushes to take their money out and the bank goes under.

Statistically, only a small number of customers might request their money back at any given day and in future days. Statistically, it follows, the bank could use some of that money in a number of ways, including making loans to other people or businesses and purchasing securities.

Mismatching mental models and regulation

There is a fundamental mismatch between most people's mental model of what a bank checking account is (a "safe box in a vault”) and the actual workings of the product (a "loan to the bank that you can call back instantly"). When one deposits money in a bank, one's actually lending said money to the bank. Only, it's an (unsecured) lending facility that pays zero interest and that must be repaid instantly shall the customer request it. Similar, but also radically different.

But customers don't think that way. Customers think they've placed their money in a digital safe box, where the money is kept until they ask for them. Customers who deposit money in a checking account don't assess credit risk the way investors who buy a bond from the same issuer do.

(Many critics to the FED + FDIC's actions (guaranteeing all deposits regardless of size) think checking account depositors should bear the loss of a bank's failure, as if they were investors in its bonds. I don't agree with this view.)

This mental model mismatch seems to be a good reason to reassess how the product works (i.e., regulations around it).

Reserves

Under Federal Reserve rules, banks operate by using a system called fractional reserve banking. For every dollar the bank gets in deposits, it has to keep a fraction of that dollar deposited with the central bank, i.e., the FED in SVB's case, in part so it can meet the demands of customers who want to withdraw their money.

Reserve levels, i.e., the percentage that has to be kept with the FED, are set according to two main variables. The first is the FED's perception of what's, statistically, the most that can be withdrawn by customers in a short time frame; the second is the FED's predisposition to ease or tighten monetary conditions [1].

Depositor's Dilemma

The prisoner's dilemma is a scenario in game theory where two individuals are arrested for allegedly committing a crime together. They are held in such way as to not be able to communicate with each other. The figurative prosecutor makes an offer to each prisoner: if you confess and your partner remains silent (i.e., doesn't confess), you'll get a lighter sentence, let's say 1 year, while your partner will get a heavier sentence, let's say 5 years. If both of you confess, both get a moderately heavy sentence, let's say 2.5 years. Finally, if both of you remain silent, both of you get the lighter 1 year sentence.

It follows that each prisoner must decide whether to confess (hoping the other partner keeps quiet) or remain silent (again hoping the other partner keeps quiet). But one can only hope, without knowing for sure what the other partner will do. The dilemma arises because each prisoner is individually better off by confessing, regardless of what the other does, so as to "guarantee" either the lightest or the moderate sentence. However, the logic applies to both prisoners, so both prisoners will tend to confess, and then receive the worst outcome of 5 years in prison, showing how individual rationality can lead to a worse outcome for both when they are unable to cooperate or communicate with each other.

The prisoner's dilemma has been often used as a metaphor for the dilemma faced by depositors in a potential bank run (let's call it the Depositor's Dilemma): In a bank run situation, each customer of a bank is rationally compelled to withdraw their money as fast as possible. If one doesn't and other customers do, there'll be no money left for everybody.

That's probably the similarity where the confusion comes from. But it's a pretty imperfect comparison [3].

Going forward

As a result of the failure of SVB (and Signature) there's the risk that other regional banks are affected with similar runs on their deposits. The risk of such contagion is surely contributing to First Republic Bank's shares dive into the abyss:

Investors probably think other regional banks may i) hold losing positions in fixed income [4] or ii) face huge deposit withdrawals in the coming days.

One huge problem that needs to be solved by U.S. regulators is that these movements tend to become vicious cycles: shares and bonds plummet, depositors become scared, withdrawals skyrocket, shares and bonds fall even further, and so on and so forth, a cycle which took a matter of days in the 30's - i.e., was already really fast - and has been further compressed by the internet, smartphones, and Twitter.

Inflation and interest rates

An interesting second order effect of this whole crisis is the position it's left the FED in, or, whether the FED will change the way it has been dealing with inflation.

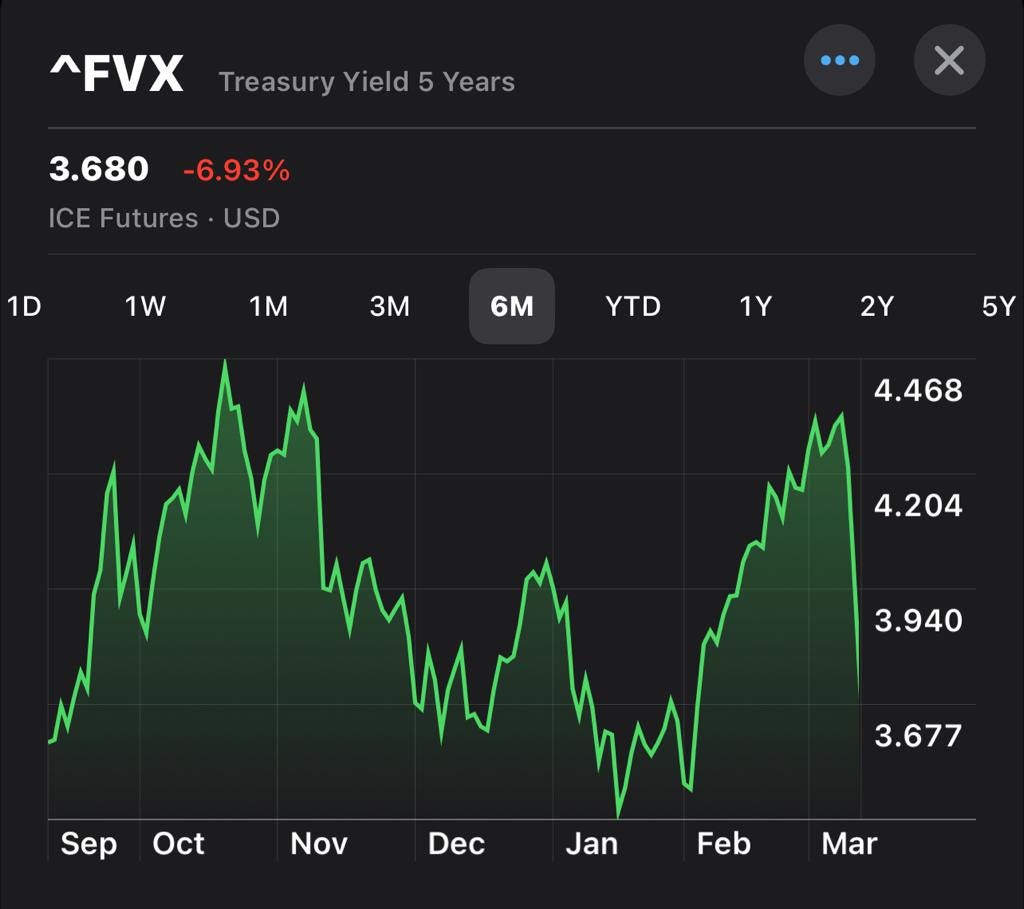

The path until now has been to tighten monetary conditions, by raising the FED funds rate and refraining from buying government bonds from banks (quantitative tightening). But tighter monetary conditions dry up liquidity and may make the lives of regional banks even tougher. On the other hand, loosening monetary conditions (and helping the banking system remain stable) could make taming inflation even harder than it already is - rates haven't fallen significantly even on the back of one of the steepest rate hike cycles ever. The market seems to believe that the FED will indeed change course, as seen by the following graph, of the yields of 5-year treasury bonds:

It will be certainly fun to watch how these events unfold.

Notes

[1] The FED has a number of tools at its disposal in pursuit of its mandates of inflation control, economic growth - subordinate to inflation being under control - and financial system stability. The main one, of course, is the so called FED funds rate, the rate at which the FED loans money to banks on an overnight basis, which in practice serves as a floor for interest rates charged in an economy; the second is purchasing and selling government bonds from banks (more about this tool here and everything else on this article here); the third is setting reserves on cash balances, commonly referred to as deposits. If the reserves are higher, a smaller fraction of marginal deposits can be lent out. Conversely, if the reserves are lower, a higher fraction of marginal deposits can be lent out [2].

[2] We're not going into the fact that money lent out can be then deposited at another bank - or even the same bank - and, aside from reserves, be lent out a second time, and on, and on, and on. The effect of reserve requirements on this virtuous or vicious cycle is called "velocity."

[3] For example, there's a timing component in the Depositor's Dilemma that's absent in the Prisoner's. In a bank run, you're not better off only by withdrawing your money: you have to do so before the bank runs out of it, which means doing so before other customers.

[4] The whole problem with SVB started with the risky decision by the bank's management to invest a huge portion of their cash in very long-dated (10 year) U.S. treasuries and mortgage-backed securities (MBS). Management found a bit of yield in those bonds (it purchased the treasuries at a yield-to-maturity of 1.5%) when FED funds were at 0% or thereabout. But FED funds (and the whole rest of the yield curve) climbed fast as the FED sought to fight inflation, and the value of those treasuries took a crazy dive [5]. This loss wasn't being accounted for because the bank used this crazy accounting gimmick to not mark the bonds to market - it placed the bonds in accounts meant for securities that are going to be held until their maturity (i.e., for ~10 years). BUT, and there's always a but, the bank changed its mind regarding holding to maturity and decided it needed to sell the bonds, and by selling them, they sealed the loss, and had to announce it to investors.

[5] The same logic applies to MBS, which were, for different reasons, the culprits of the 2008 financial crisis.